Smokeless Tobacco and Health: The AHA Statement: "Just Say No"

Last Updated: May 11, 2023

In its statement, Impact of Smokeless Tobacco Products on Cardiovascular Disease: Implications for Policy, Prevention, and Treatment, the American Heart Association (AHA) offers a timely review and clear guidance on smokeless tobacco products. Tobacco has long been used in smokeless forms; in fact, until the advent of the Bonsack cigarette-making machine and the modern tobacco industry over a century ago, tobacco was predominantly used in smokeless forms. Worldwide, smokeless tobacco use remains common, for example, accounting for the majority of tobacco use in India.[1] At present in Sweden, more men use snus, a form of moist oral tobacco, than smoke cigarettes.[2]

In the United States, cigarette smoking has been the predominant form of tobacco use for more than a century, but smokeless tobacco use has persisted, particularly in rural areas and among males. This new statement is published as smokeless tobacco products are proliferating and the marketplace for nicotine-containing products is becoming increasingly diverse. One motivation for the tobacco industry to market smokeless products is the increasing coverage of the population by smoking bans, which are known to motivate less smoking and increased quitting.[3] Smokeless products provide the nicotine-addicted cigarette smoker with a way to obtain nicotine throughout the day, without needing to leave the workplace to smoke. Snus, for example, is primarily being sold in the United States as a sachet in a small and readily carried can and marketed with such slogans as "No spit. No smoke. No boundaries" and "Pleasure for wherever."[4] One consequence of the availability of such products may be a lessening of the motivating force of workplace bans for reducing smoking and quitting. Rather than quitting, cigarette smokers may substitute a smokeless product in those situations where smoking is not possible.

However, if smokeless products are less risky than cigarettes, the health risks of tobacco use may be reduced for individuals who are nicotine addicted and unable to quit permanently. The AHA statement addresses this issue, based on its evaluation of the properties of smokeless tobacco and the mechanisms by which it could increase risk for cardiovascular disease, and on its review of the available epidemiological information. The conclusion is offered that the risks for cardiovascular disease associated with smokeless tobacco use "are lower" than those from smoked products. Beyond cardiovascular disease, smokeless tobacco products are a long-established cause of oral cancer and they also increase risk for esophageal and pancreatic cancers.[5,6]

All-cause mortality provides an informative indication of the overall impact of the use of a tobacco product on health. For smokeless tobacco, the relevant epidemiological information is limited and not reflective of the consequences of using the current range of products. Mortality patterns have been examined in users of smokeless tobacco products in several cohort studies.[7] Five studies show increased risk for all-cause mortality in comparison with never smokers. The magnitudes of the increases ranged from about 20% to 40%.

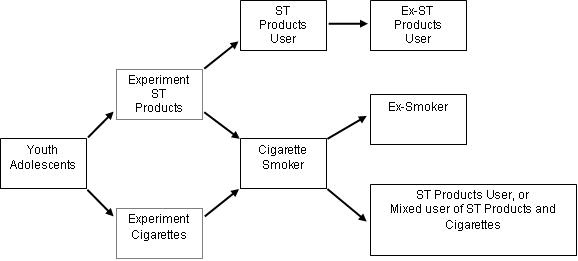

The AHA statement takes on the difficult policy choice of whether to recommend smokeless tobacco use as a "harm reduction" strategy for cigarette smokers - a choice that needs to be based in a careful weighing of the benefits to individual smokers who cannot stop against the potential for harm to the population because of sustained nicotine addiction and recruitment of new tobacco users through the "gateway" of smokeless products (Figure 1). Harm reduction as a strategy for reducing the risk of tobacco use has been a contentious topic, with the poles of the debate in full disagreement. Those favoring advancing smokeless tobacco as a harm reduction strategy point to the lower disease risk in comparison with continued smoking of cigarettes, while those not in favor offer concerns about reduced quitting of tobacco use and enhanced initiation. Scenario-based modeling has been carried out to evaluate the health impact of promoting smokeless tobacco for harm reduction; the results are mixed and model dependent.[8,9]

Figure 1. A model of patterns of use of smokeless tobacco products and cigarettes. ST Products = Smokeless tobacco products (snus, snuff, chewing tobacco, etc.)

The AHA statement does not formally assess risks versus benefits but offers a firm recommendation against use of smokeless products as a harm-reducing alternative to cigarettes. Some will disagree with this recommendation, as there has been an unnecessarily acrimonious debate within the public health community on harm reduction strategies based in use of smokeless tobacco products. The AHA's recommendation is fully consistent with its commitment to tobacco control and health and uncertainty as to the long-term risks of new products.

Its recommendation extends to clinicians who are instructed to "...discourage use of all tobacco products." This is the appropriate recommendation because the physician's goal for patients should be cessation of use of any nicotine-containing product. Physicians may be faced with patients who do not want to quit using tobacco and who view switching to smokeless tobacco as a safer alternative to cigarettes. For such patients, the physician should be prepared to inform them as to what is known about the risks of smokeless tobacco and the consequences of sustained nicotine addiction. The AHA statement is a useful starting point for that purpose.

The AHA statement makes the inevitable call for more research and offers its recommendations for setting priorities. The three topics are less reflective of a need for "research" than for ongoing surveillance of the public health consequences of availability and marketing of smokeless tobacco products. We need to make certain that ongoing surveillance systems are sensitively calibrated to track the implications of smokeless tobacco for initiation and cessation. Ongoing research is needed on the consequences of changing products for risks to health. Epidemiological studies of disease outcomes will not be sufficiently timely for this purpose, given the timeframes over which exposure to tobacco increases disease risks. The potential risks of smokeless products may be best gauged by tracking of key biomarkers within a mechanistic framework.

The AHA statement is a timely and needed assessment of smokeless tobacco and cardiovascular disease risk. Its recommendations parallel those of other organizations that oppose use of smokeless tobacco as a harm reduction strategy, including the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids,[10] the National Cancer Institute,[11] and the American Cancer Society.[12]

Citation

Piano MR, Benowitz NL, FitzGerald GA, et al. Impact of smokeless tobacco products on cardiovascular disease: implications for policy, prevention, and treatment. A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f432c3. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/122/15/1520.full

References

- Reddy KS, Gupta PC, eds. Report on Tobacco Control in India. Mumbai: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, 2004.

- Foulds J, Ramstrom L, Burke M, et al. Effect of smokeless tobacco (snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tob Control 2003;12(4):349-359.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006.

- Biener L, Bogen K. Receptivity to Taboka and Camel Snus in a U.S. test market. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11(10):1154-1159.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Smokeless tobacco and tobacco-specific nitrosamines. IARC Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, Vol. 89. Lyon, FR: IARC, 2007.

- Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, et al. A review of human carcinogens - Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncol 2009;10(11):1033-1034.

- Colilla SA. An epidemiologic review of smokeless tobacco health effects and harm reduction potential. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2010;56(2):197-211.

- Gartner CE, Hall WD, Vos T, et al. Assessment of Swedish snus for tobacco harm reduction: an epidemiological modelling study. Lancet 2007;369(9578):2010-2014.

- Mejia AB, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Quantifying the effects of promoting smokeless tobacco as a harm reduction strategy in the USA. Tob Control 2010;19(4):297-305.

- Boonn A. Smokeless tobacco in the United States. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Available at: http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0231.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2010.

- National Cancer Institute. Smokeless Tobacco and Health: An International Perspective. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1992.

- American Cancer Society. Smokeless tobacco and how to quit. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/CancerCauses/TobaccoCancer/SmokelessTobaccoandHowtoQuit/index. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Science News Commentaries

-- The opinions expressed in this commentary are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association --

Pub Date: Monday, Sep 13, 2010

Author: Jonathan M. Samet, MD, MS

Affiliation: